for Visual Music Artists, Writers, and Venues

-

Accutek Packaging

- Female

- Vista, CA

- United States

- Blog Posts

- Discussions

- Events

- Groups

- Photos

- Photo Albums

- Videos

RSS

Packaging Material Waste Reduction in the USA: How Line Design Cuts Scrap Without Slowing Output

Material waste in packaging lines rarely explodes into a crisis. It usually builds slowly in bins of rejected bottles, crooked labels, and product that must be dumped after a bad fill.

Each loss looks small by itself. Together, these losses cut into profit.

Many plants still treat scrap as the price of running fast. Crews chase speed while accepting waste as normal. Across the United States, this habit raises costs, adds compliance risk, and weakens sustainability goals.

This article explains where packaging material waste really comes from, why it persists on modern packaging machines, and how better line design can cut scrap on packaging machinery without slowing production.

Why material waste matters in the USA

Material waste is more than an environmental issue. It is a financial and operational risk.

In U.S. plants:

- Labor is expensive.

- Disposal rules are tightening.

- Brands face growing sustainability pressure.

When scrap rises, total costs rise even faster.

Most waste does not start with bad materials. It starts with how the line behaves during real production.

Where packaging waste usually begins

1) Unstable infeed

Uneven bottle spacing or tipping disrupts filling and labeling downstream.

2) Fill instability

Pressure swings or pump drift create overfills and underfills that must be dumped.

3) Label problems

Wrinkled or crooked labels often force relabeling or scrap.

4) Changeovers

New SKUs usually create waste until the line stabilizes.

5) Restarts

Every stop and restart creates a short burst of defects packaging machines.

A few rejects per hour may look minor. Over a full shift, they add up to major losses.

How small waste events become big losses

One rejected bottle feels small. Hundreds per shift are not.

How scrap compounds in one shift

| Waste source | Frequency | Scrap per event | Total scrap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Label misalignment | 6 per hour | 3 bottles | 144 bottles |

| Fill drift rejects | 4 per hour | 2 bottles | 96 bottles |

| Restart defects | 5 per hour | 4 bottles | 160 bottles |

| Total lost units | — | — | ~400 bottles |

Most plants never classify this as “material loss,” yet it is real money.

Why teams misdiagnose scrap

Many teams blame materials or operators when scrap rises. This usually misses the true cause.

In practice, scrap most often comes from:

- Unstable flow

- Weak restart behavior

- Poorly matched packaging machinery speeds

Fixing materials or retraining people rarely solves these problems.

Common assumptions vs reality

| Common belief | What usually causes waste |

|---|---|

| “The labels are bad.” | Inconsistent |

…

The post appeared first on Accutek Packaging Eqpt.: Filling, Capping, Labeling Machines.

Packaging Machine Downtime in California: Why Minor Stops Create Major Losses

Packaging lines rarely break in one big way. They lose time little by little.

A conveyor pauses. A sensor trips. A bottle tips. An operator clears it. The line restarts. Production continues. Nothing looks serious. By the end of the shift, a lot of capacity is gone.

These short stops feel normal in many facilities. Teams clear them fast and move on. Because nothing breaks, the loss is rarely logged as downtime. Yet these tiny pauses quietly drain productivity.

This article shows how small stops add up, why this hurts California manufacturers, and what smooth lines do differently.

Why “Invisible Downtime” Costs More in California

California makes small losses very expensive.

- Labor costs are high, so every lost minute matters.

- Compliance rules slow troubleshooting and restarts.

- Frequent SKU changes cause more brief stops.

- Automated lines have many sensors that can pause the line.

When minutes are costly, short stops become a real business problem.

Where Micro-Stoppages Usually Start

1) Unstable infeed

Uneven spacing, tipped bottles, or poor orientation can trigger downstream pauses.

2) Overly strict sensors

Poor placement or aggressive settings create nuisance stops that are not truly needed.

3) Speed mismatches

When machines run at different real speeds, one station slows the entire line.

4) Slow restarts

After each stop, the line needs time to stabilize — multiplying the real loss.

Takeaway: These are not maintenance breakdowns. They are system behavior problems.

How Small Stops Become Big Losses

One 10-second stop feels small. Ten in an hour are not.

How micro-stoppages add up in one shift

| Event | Frequency | Time lost per event | Total loss per shift |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short sensor fault | 8 per hour | 8 seconds | 32 minutes |

| Minor jam clear | 4 per hour | 15 seconds | 24 minutes |

| Restart stabilization | 6 per hour | 10 seconds | 36 minutes |

| Total hidden loss | — | — | ~90 minutes |

Most facilities never record this as downtime, yet nearly two hours of production disappear.

Why Standard Downtime Tracking Misses the Problem

Many California plants track only major breakdowns. They typically miss:

- Stops under 30 seconds

- Restart delays

- Small operator interventions

- Temporary speed cuts

Dashboards look fine — but real output is still lower than it should be.

What gets measured vs what truly matters

| What is commonly tracked | What usually drives losses |

|---|---|

| Major breakdowns | Frequent micro-stops |

| Scheduled maintenance | Restart delays |

| Planned downtime | Operator micro-interventions |

| Peak line speed | Real average throughput |

How Line Design Amplifies Small Problems

…

The post appeared first on Accutek Packaging Eqpt.: Filling, Capping, Labeling Machines.

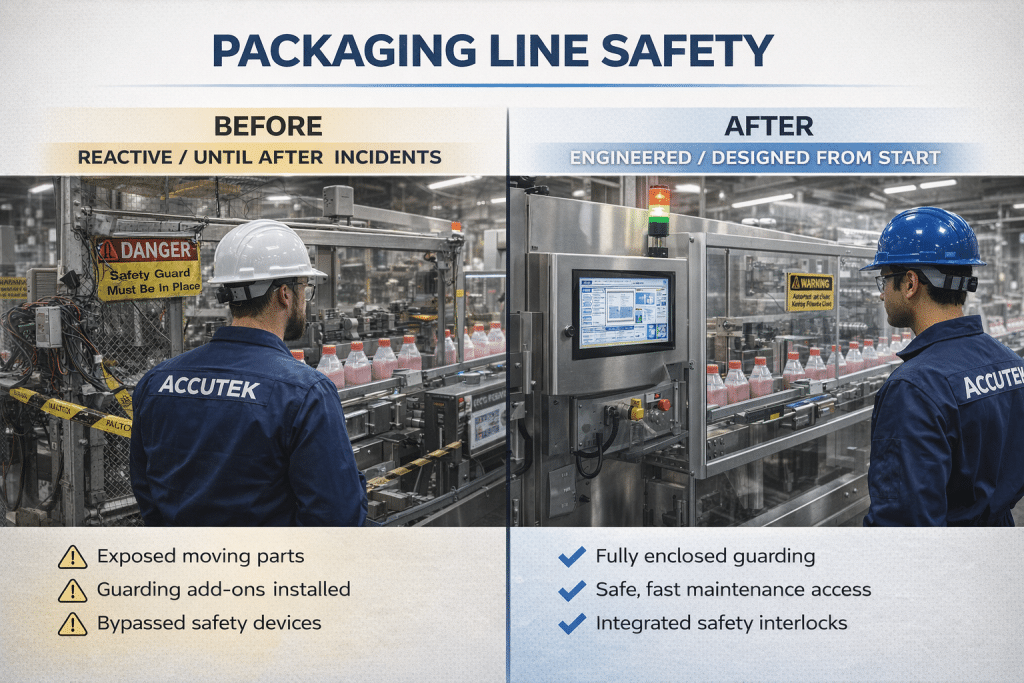

Packaging Machine Safety & Risk Mitigation in California: Engineering Practices That Protect People and Productivity

High-speed packaging machines are often built around one overriding objective: move product as fast as possible. Only after the line is running do many facilities fully address how people interact with that speed. Guards are added late, procedures are layered on after incidents, and safety becomes something managed through training rather than designed into the system.

That sequence quietly embeds risk into everyday operations. When nothing goes wrong, production looks efficient. When something does go wrong, the consequences are severe: emergency stoppages, investigations, retraining, lost shifts, and schedule disruption that can ripple across an entire plant. In modern automated packaging, safety cannot be treated as a secondary concern — it must be a core engineering requirement.

This article examines why traditional, reactive safety practices struggle in high-speed packaging environments, how engineering-led risk mitigation reshapes line behavior, and what separates facilities where safety protects productivity from those where it repeatedly interrupts it.

Why Safety Carries Extra Weight in California Manufacturing

Packaging operations in California operate under conditions that make weak safety design especially costly:

- Cal/OSHA enforcement increases exposure to penalties and shutdowns.

- High labor costs amplify the impact of injuries and lost shifts.

- Highly automated lines introduce new types of mechanical and electrical risk.

- Complex product portfolios require frequent adjustments and interventions.

- Brand and recall sensitivity raises the stakes of operational incidents.

In this environment, safety must do more than satisfy minimum compliance — it must reduce risk through thoughtful machine and line design.

The Problem with After-the-Fact Safety

Many facilities still approach safety reactively, retrofitting protections only after equipment is installed or an incident occurs. While this may satisfy basic requirements, it rarely produces truly safe or efficient operations.

Common outcomes include:

- Guards that block visibility or maintenance access.

- Operators bypassing safety devices to keep the line moving.

- Frequent emergency stops that disrupt production.

- Longer troubleshooting cycles due to poorly integrated safeguards.

In practice, reactive safety treats symptoms rather than root causes.

Reactive vs Engineered Safety

| Dimension | Reactive safety | Engineered safety |

|---|---|---|

| When safety is considered | After installation | During line design |

| Guard placement | Improvised | Purpose-built |

| Operator behavior | Workarounds common | Safer defaults |

| Downtime impact | High | Low |

| Compliance risk | Variable | Consistently lower |

Where Risk Most Commonly Emerges on Packaging Lines

Safety hazards tend to cluster around predictable points in the process rather than appearing randomly.

1) Infeeds and transfers

Manual interventions most often occur where containers enter or move between machines.

2)

…

The post appeared first on Accutek Packaging Eqpt.: Filling, Capping, Labeling Machines.

Gifts Received

Accutek Packaging has not received any gifts yet

Accutek Packaging's Page

Profile Information

- What's your interest in Abstract Music Visuals?

- writer/scholar

© 2026 Created by Larry Cuba.

Powered by

![]()

Comment Wall

You need to be a member of The Visual Music Village to add comments!

Join The Visual Music Village